How I Work

Your work is yours. It’s the product of hours, months, or years of hard work, research, writer’s block, peer reviews, and sleepless nights (and countless cups of coffee). The thought of an editor cutting through your writing is daunting. I’m a writer myself, so I get that. But a good editor is not your pen-wielding enemy. A good editor is your ally. Your advocate. Your eagle eyes. Your “Yes! That’s what I was trying to say!” A good editor is the single greatest gift you can give to yourself in the process of publishing your work.

What’s more, an editor (a skilled one, anyway) won’t alter your voice, stifle your creativity, or convolute your meaning. In my experience, those are the crux of any writer’s dread, fiction and nonfiction alike. As your editor, I want you to know how I work and to be comfortable at every stage of the process.

Before taking “pen to paper,” I always do a pre-read. This takes a minute, yes, but it’s far better to know what’s what before I start redlining anything. Most seasoned editors do a pre-read; we’ve figured out that it’s far more efficient in the long run. (Be wary of an editor who does not.)

For any project longer than a page or two, I create a “cheat sheet”—a project-specific style guide. As I work my way through your text, I take notes on project-specific names and terms, odd or distinctive spellings . . . anything notable or idiosyncratic that’s likely to reappear in your manuscript. This saves a ton of time otherwise spent in find/replace mode.

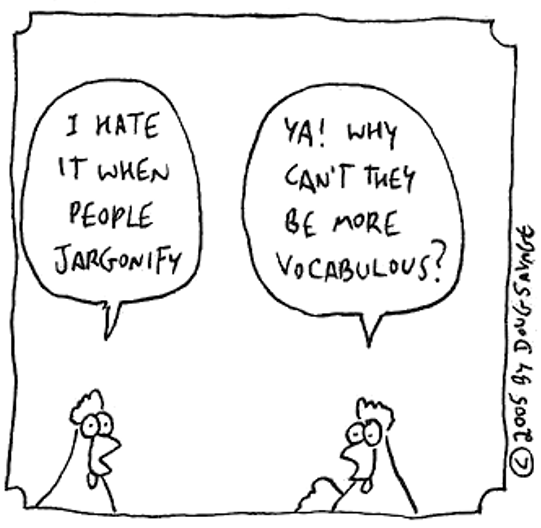

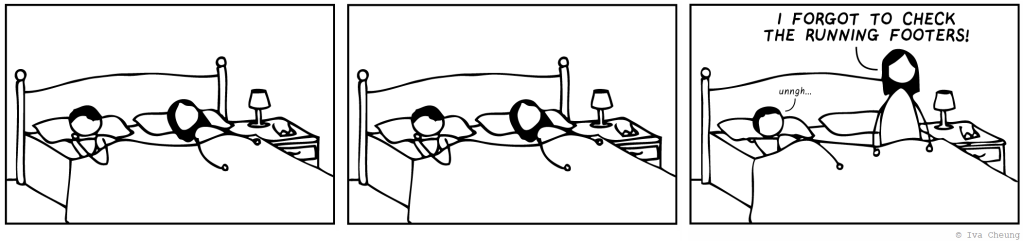

Speaking of find/replace, before I start going line by line, I always do a quick search for routine offenders like double spaces, punctuation blips, irregular spacing, headers and footers—basic issues that nearly every project harbors at least one or two of.* As I’m going through, I keep my editorial checklist of all these little gremlins handy as a reminder to dot all the i’s and cross all the t’s.

I offer three different levels of service: content editing (also called line editing or substantive editing), copyediting, and proofreading. Click here for a broader explanation of what each entails. Most projects involve one editing pass, an author review, entry of the changes, and final manuscript delivery. Some projects need more than one back-and-forth round if you add or change your text substantially during the process. We aren’t finished until you’re satisfied with your final manuscript. I generally only accept one project at a time in order to give my clients the full attention they deserve.

I edit in Microsoft Word, the industry standard. I do not work in Google Docs—it’s a cumbersome and problematic user interface that ends up costing extra time and aggravation and wasting clients’ money. I always edit with track changes enabled so that you can see everything I’ve done, and I annotate the text with comments and queries for you to address. I will proofread in either Word or Adobe Acrobat; Word is preferable unless it’s a true proofread (i.e., in page proofs). I use the Chicago Manual of Style (17th edition) and Merriam-Webster’s almost exclusively, along with any house style my clients’ publishers use. Those two resources are by far the most common and accepted.

A note about style: it matters. Style guides weren’t invented to stifle and annoy you; they exist to help readers by making writing consistent. That said, there is some flexibility from genre to genre. An academic volume published under a university press’s emblem should follow whatever style guide that press adheres to as well as any house style. Any professionally run publisher will have a house style. (Be wary of one that does not.) Some publishers are more rigid than others when it comes to adhering to style, and the style rules are somewhat more flexible with fiction and poetry, where there’s a bit more space for an author’s individual style and voice. Above all, a work should always be consistent within and throughout itself.

The bottom line, taken verbatim from Chicago, is this:

“A light editorial hand is nearly always more effective than a heavy one. An experienced editor will recognize and not tamper with unusual figures of speech or idiomatic usage and will know when to make an editorial change and when simply to suggest it. . . . An author’s own style should be respected, whether flamboyant or pedestrian. On the other hand, manuscript editors should be aware of any requirements of a publisher’s house style.”

What that paraphrases to is that you want an editor who will respect that your work is yours while making it the best it can be. Publishing your work is a daunting and exciting process. I’d love to walk through it with you.

* To the eagle-eyed potential client: yes, I gleefully ended that sentence in a preposition. I’ve had rows with my husband (a linguist) over this archaic grammatical constraint. Chicago sides with Winston Churchill, who once scoffed at being corrected for doing so: “That is the type of arrant pedantry up with which I shall not put” (Bryan A. Garner, ed., Garner’s Modern American Usage, 4th edition [New York: Oxford University Press, 2016], 476).